Top Stories of 2024: Proven approaches for talking about polarizing topics at work

Strategies for taking the temperature down amid rising employee activism and polarizing discourse.

This story was originally published on May 8, 2024. We’re republishing it as part of our countdown of top stories of the year.

As campus protests and corporate activism around the Gaza war continue to dominate coverage and conversations, it seems like no organization handled its response properly.

While Google CEO Sundar Pichai attempted to justify the firing of employee activists a couple of weeks ago, police cleared an occupied building at Columbia University last week and arrested dozens of protestors. As stories of student encampments and ongoing protests continue to make headlines, communication from university leaders has been minimal. In a multifaceted conflict that engages stakeholders at an intersectional level, many leaders seem to take the route of saying less.

Brown President Christina H Paxson’s letter to the community last week seems like a step in the right direction, however, reminding communicators that our rule requires mindfulness for how our words can influence stakeholder behavior. These protests also raise questions over how well-equipped institutional DE&I programs are to address intersectional conversations among stakeholders when neither group involved is a monolith.

To that end, it may be high time for communicators to put on our coaching/ facilitator hats and understand the role we can play in minimizing polarization at work.

To learn how comms can get there, we spoke to Mary-Frances Winters, founder and CEO of The Winters Group about her landmark book, “We Can’t Talk About That at Work: How to Talk about Race, Religion, Politics, and Other Polarizing Topics,” which was republished in an updated edition this year with additions from author Mareisha N. Reese, president and COO of The Winters Group.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

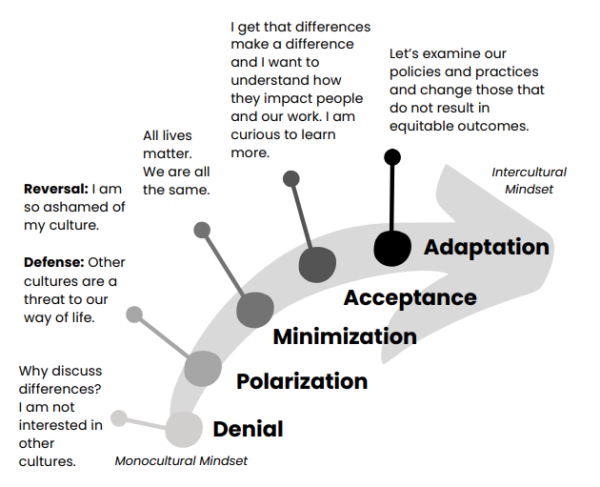

Justin Joffe: Let’s start by talking about the Intercultural Development Continuum as it seems so foundational and relevant in this current moment. How would you coach someone, a communicator at a university for example, to use this concept engaging with different stakeholders like student activist groups, maybe on both sides of the Gaza war protests, alongside alumni groups and others who are voicing their pain and frustrations without working with comms? When we’re advocating for comms to be a unifier, how can they use this continuum as a starting point?

Mary-Frances Winters: The first thing we have to recognize is that these kinds of topics and issues that people are dealing with right now, they’re very emotional. And so facts don’t work. When the emotions are already really, really high, getting people to pause is the first thing.

Once that pause happens, we can get people to do some self-reflection. So what’s going on with me right now and why do I feel so strongly about this? What has been my lived experience? Am I listening to others? Am I willing to listen?

Courtesy of The Winters Group, Inc., adapted from IDI, LLC.

The Intercultural Development Continuum is a normal distribution curve. It says that there are about 2% of people who at this place called “denial”—”I don’t know – anything, I don’t want to know anything. .” And then there are about 15% of the people are at this place called “polarization.” Polarization comes after you learn a little something, and you’re like, “. Why would they do that. It is not like we would do it and it is not as good or it is wrong. ” That’s the “us and them,” and that’s where we’re at with so much in our world today. It is a simplistic way of looking at the world—in binaries..

What we have to do is get people to the third place on the continuum, “minimization,” which asks, “What are our similarities? What do we all care about?” If we think about what’s happening with Palestine, Gaza and Israel, and if people just pause a minute If we can all agree that killing innocent people is wrong, no matter who the people are, we have a place to start a conversation.

JJ: I think the language sometimes contributes to the polarization, too. “Genocide” is a loaded word for many Jews who lost family or were educated about the Holocaust, whether or not it’s accurate. I’m trying to sit at this intersectional place where I’m seeing that public discourse turns up the temperature, while advocating for language and the words we use. I agree with you, but I think the language and positioning is a big part of it that comms doesn’t always take ownership of.

MFW: When we’re doing our own self-reflection, what is my interpretation when I hear the word “genocide,” what comes to mind for me? Does something else come to mind for someone else? Like “From the river to the sea,” that’s the other thing I hear about when I talk to my Jewish friends. If we can have a conversation about what it means when I say that or when I hear that, it still may be inappropriate to say it, but you know that’s not what I meant. We do have to consider the intent and the impact. If the impact is harmful, then we need to change the language.

JJ: 100%.

MFW: When administrators or leaders at universities are trying to lower the temperature, the first thing in terms of bringing people together is coming at it with respect—respect for the humanity of all people. We start here and think from a self-awareness perspective—that’s our first stage on this continuum. Really think about why you feel so strongly.

The other piece of our model is, do I even know enough to be in this conversation? Have I done my research and homework? Have I looked at all sides of it, or am I coming from an emotional place?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie speaks about the danger of a single story.

There are some people on either end of the normal distribution curve you’re just not going to get to. They’re the extremes.

JJ: Communicators have to work with ‘the moveable middle.’

MFW: That’s exactly right. The normal distribution is that 68% of people. It’s a statistical thing—you’ve got about 2.5% of the people on either tail of this, then you’ve got about 68% of the people in the middle on the Intercultural Development Continuum. Sixty-eight percent are typically at minimization, meaning, “I think we’re all the same, or I think we should be all the same.” But then we have people who are now at this polarization where it’s either this or that, not recognizing the complexity and the nuance of what is going on.

It’s not a this or that—let’s sit down and talk about what we agree on. What is your desired outcome? Ceasefire? For me, the desired outcome would be no war because I’m a pacifist. But in an inclusive world, I have to recognize that other people have the right to a different opinion. What are the things we can agree on? It’s getting to that shared humanity, shared mentality and shared mindset.

JJ: “Shared humanity” is a phrase we’ve heard a lot, too. Microsoft put it out in their post after October 7, and it’s a great example of bridging language.

MFW: Bridging language, exactly right. When you get on this Intercultural Development Continuum, when you get from minimization to acceptance, that’s where the place of curiosity comes in. This model is saying that the more you understand, the more knowledge you have. The more interaction you have with different cultures and different philosophies and different ideas, the greater your capacity to hold complexity.

JJ: What is reciprocal empathy to each of you and how can managers and communicators know when they’ve reached this point in the continuum?

MFW: Sometimes we say that we want to center the experiences of those most impacted. My belief is that we’re all impacted by racism, antisemitism, homophobia, all of those things. We’re all impacted whether we’re a member of that group [and] the world is impacted by that. And so, in the spirit of your respecting and honoring humanity, I have empathy for an individual who might not have the knowledge, or might be ignorant of something, as opposed to wanting to punish that person. We do a lot of punishing these days if someone gets it wrong.

So I’m advocating for this idea of reciprocal empathy, it’s not complex. Certain conditions have to be in place, and one is that the person who has, not with any malintent, said or done something wrong needs to genuinely apologize for that. It can’t be like, “I didn’t mean anything by that” or “You’re being too sensitive.” Respect is the condition that has to be in place for reciprocal empathy to occur. I can empathize that you just didn’t know and you can learn more about this. Reciprocal empathy happens because we’re going to be so benevolent that we just kind of empathize with everyone.

But there has to be some mutuality if you’re going to have an inclusive conversation. It can’t be the extreme of, “Well, I’m the oppressed one, and you are a member of a group that’s been the oppressor, so you don’t get any consideration.”

JJ: This echoes a concept that I spoke with a DE&I facilitator at after October 7th, the “oppression Olympics” spiral wherein two historically oppressed groups can go tete-a-tete with one another and compare tragic points in history or awful things that happen. This idea of reciprocal empathy seems to tap the same human inclination to snowball but use it as a bridge to come to a place of understanding.

Mareisha N. Reese: It’s that ability to understand the other person more. So even if you didn’t get to a point where you had full total agreement, hopefully you’ve learned from the other. Maybe you have moved now a little bit closer to the right on the Intercultural Development Continuum because you’ve talked with someone who had different beliefs and may be your cultural other, and you’ve shared some things, you’ve shared lived experiences and are able to understand that better. And hopefully it’ll spark whoever’s in that conversation to continue to learn more.

Now’s the time to get ready, especially within your organization, because you should not be creating that culture and environment when something happens. The system to have these conversations must happen before.

Pick up the expanded second edition of “We Can’t Talk About That at Work: How to Talk about Race, Religion, Politics, and Other Polarizing Topics” here.