Top Stories of 2024: Effective approaches to influence employee behavior

Tips for driving behavior by seeking commitment, not compliance.

This story was originally published on June 28, 2024. We’re republishing it as part of our countdown of top stories of the year.

Marketers often measure the success of their efforts to influence customer or client behavior. Communicators? Not so much.

There’s wisdom in looking at driving behaviors from a personal, relationship-driven lens and a larger, organization-wide lens. Thinking from both perspectives can ensure that stakeholders are effective partners working toward shared goals and the larger goals of the business.

Here are tried-and-true tactics from two experts in strategic communications and organizational development to get what you need from colleagues and clients alike.

Communications alone don’t drive behaviors

Working on projects even with other comms teams and departments is a quick reminder that all leaders share similar challenges.

“We’re trying to use our expertise and our lens to help drive the business forward,” says organizational development (OD) expert and consultant Melissa Janis. “But we are very often mired in the business as usual, rather than trying to be strategic, which is really where the value is.”

And so, there’s a tendency to communicate to employees and make the case for change, and then be surprised that the new approach has not been sufficiently adopted.

One of the tools available in the OD toolkit is the structural intervention, which is a change in the corporate environment to guide behaviors and outcomes. You can’t expect communication alone to drive a significant change in behavior. Janis explained with the example of speeding drivers on a street behind her house.

“There’s this enormous sign that says the speed limit is 20 miles an hour, but there’s no way anybody goes 20 miles an hour on the street though it’s a big reminder,” she explained. “It’s a long road and you think it’s desolate, so you pick up speed.”

Despite the clear communication, people continued to speed until two stop signs were installed. Now drivers slow down because they have to. While the communication sets the expectation, the stop signs serve as a structural intervention that elicits the desired behavior.

Driving behavior by seeking commitment

Communicators who drive effective internal change can choose to push people toward a behavior or pull them toward it. Janis frames it as the distinction between compliance and commitment.

Seeking compliance often seems like the easiest way to get people to make a change, but it might just waste time and money,” she said.

“If you’re trying to drive attendance to a leadership development program, for instance, telling people it’s mandated may just result in them showing up and not paying attention. Worse yet, the participation of people who would have willingly come and bought in by choice is tainted.”

Instead, aim for commitment by deeply understanding participant needs and framing messaging to help them make good choices.

Thinking about the message and the behavior it’s driving requires visibility and omniscience. Janis refers to this perspective as “going to the balcony.”

“You watch the play from above and that’s how you see what’s going on,” she said, adding that this mindset shift quickly illuminates the “what’s in it for me.” “Then, if I create a scenario where the desired behavior is the best choice, I’m going to get what I need because people will be making good choices, right?” Janis reasoned. “It may be kind of Machiavellian, but it’s instrumental to achieving the goal.”

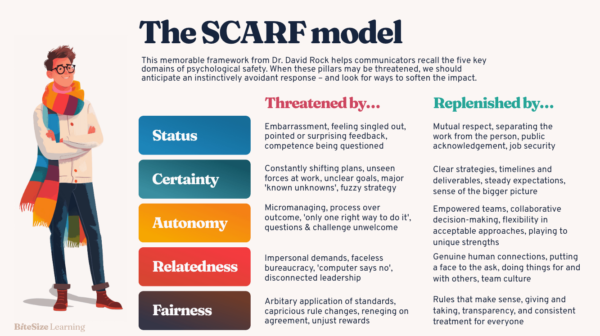

Deploying the SCARF model to change behavior

Once you understand that every style of communication has a positive or negative effect on your colleagues and employees, you can start to assess communication behaviors to consider how different styles affect the behaviors of others.

Janis cites the work of David Rock, director of the Neuroleadership Institute, that marries the five pillars of psychological safety — status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness and fairness — to leadership behaviors and communication styles.

Rock’s research found that most behaviors either threaten or replenish one of the five pillars.

Feedback lands poorly, for example, because we think managers don’t know how to do it well, Janis said. “Dr. Rock would argue that even if you do it really well, it’s still not going to land well because when you give someone negative feedback it lowers their feelings of status,” she said. “Then they perceive it as a threat and it ignites their fight or flight response.”

Janis recommended communicators use the SCARF model as a rubric to test their messages against. “Are the recipients going to feel that they are important in this scenario? Are they clear about what the future is going to hold? Where did they have some control?”

Though it may seem tough to measure these things, you can do so with open-ended questions in engagement surveys along the lines of, “To what extent do you have autonomy over X” and “How often do you make the decisions about Y?”

Don’t underestimate the role of focus groups either, as they are both a measurement and recognition mechanism for gauging behavior. “This is what we heard and designed based on what you asked for,” Janis said. “It gives employees a sense that they were important enough to be listened to, and they had some agency over how it was going to play out.”

Building interdepartmental relationships through trust

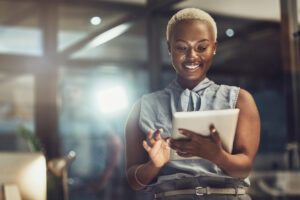

For Tommia Hayes, a digital communications specialist working in the U.S. federal government, influencing behavioral change starts with understanding the behaviors that create trust.

“I’m someone who’s very accountable—if I mess up, I’m gonna say it’s my fault,” Hayes said. “But if I’m working with someone and they mess up, I don’t try to throw them under the bus. And that’s a good way to measure when it’s time to step up.”

Setting this precedent early helps partners trust you and increases the likelihood of them taking accountability when a mistake is made.

“You have to critically assess the relationship,” continued Hayes. “Critical thinking and research go hand in hand in order to execute or even build out a strategic plan.”

On an interpersonal level, you can’t manage someone’s personality and whether they’re an introvert or an extrovert. “But I can manage how to help you think critically and become succesful,” Hayes said.

Once you understand a colleague’s behaviors, you can work with that base of understanding to advance and finalize a strategic plan.

A focus on personalization

Hayes’ experience working on integrated marketing plans taught her that personalizing your approach to individual stakeholders is also a great way to influence their behaviors toward your desired outcomes.

“It’s always someone in a department that is the lead or the owner of certain functionalities you need from that team,” she explained. “And if you can connect with that individual, everything else is like a domino effect.”

She added that too many leaders working cross-functionally try to work with the department as a whole instead of starting with one or two members of the team.

“Whether it’s a meeting or an informal conversation, just start building that relationship so they know they can trust you and see that this person from communications knows what they’re talking about. Just like me, they want to advance the mission of this organization. And they need my help. So let me help then the best way I can, and we can achieve this greatness together.”

Navigating resistance

Asking for things across the aisle might be easier said than done. Everyone feels like they’re overworked, underpaid and overwhelmed, especially as layoffs persist. Be aware that your colleagues on other teams are likely working in multiple roles they may not have been hired for, Hayes said.

Hayes also emphasized the value of setting up a productive process with someone you’d like to work with—a practical version of modeling the behavior you want to see with a student-teacher approach.

“When you’re expecting someone in another role or function to complete something, you’re expecting them to do it from the ground up,” she said. “But if you start the foundation and have them come in bits and pieces, it eliminates a lot of the stress and work. Sometimes you have to step in, do your due diligence and research.”

Taking this step on the front-end allows you to go back to the person, acknowledge they’re busy and let them know you started putting things you need into the plan or project. Then it’s as simple as asking them to take a high-level glance at your effort so you can continue the process together.

Small actions that drive big behavioral change

Both Janis and Hayes subscribe to the idea that small actions can drive big behavioral changes, an idea echoed by the work of behavioral psychologist Robert Cialdini and his book, “The Small Big: Small Changes That Spark Big Influence”, co-authored with Noah J. Goldstein and Steve J. Martin.

“Every chapter has a different influencing technique someone used to elicit the behavior that they wanted, without telling people, ‘We want you to do X,’” explained Janis.

“One example is that people are more likely to say yes if the actual delivery of their yes is out in the future. We know we’re too busy now, but we’re not good at estimating how busy we’ll be in the a few months from now.”

She cited the example of a client of hers that asked for leaders to volunteer to be mentors. All they had to do was to respond to the email with the word “yes” in response to a request to participate in mentor training three months in the future.

“We got a ridiculous number of ‘yesses’ because they didn’t have to do anything for three months,” Janis said.

Prior to that Janis’ client usually got 25% of leaders to agree to be mentors. That time, 67% wound up participating.

“Asking way in advance is a small change” she said, “but the impact is enormous.”

Justin Joffe is the editorial director and editor-in-chief at Ragan Communications. Follow him on LinkedIn.