How Zoom fatigue can hurt employees — and how to fix it

Being off-camera can help your company’s accessibility practices and stave off depression and fatigue in employees.

We’ve all taken video meetings with our cameras off. Maybe there are kids running in and out of your home office, or you didn’t sleep well the night before and are dealing with some serious eye bags. Regardless of the reason, data shows that C-suite members don’t like it when employees go camera off.

A recent study showed that 96% of executives believe remote and hybrid employees who take video meetings with their cameras off are less engaged in their work. Ninety-two percent of those execs believe that workers who are camera-off, consistently on mute in video meetings or are overall less engaged “probably don’t have a long-term future at their company.”

But other data supports the idea that having the option to turn off their own cameras during meetings can help employees feel less fatigued and reduce anxiety or depression related to staring at yourself all day.

While the desire to see your coworkers’ faces is understandable, here are a few reasons why implementing a camera-optional policy could improve overall employee wellness and satisfaction.

The true perpetrator of Zoom fatigue

Ah, Zoom fatigue, that catch-all term used to describe people’s frustration with constant video meetings that burgeoned during the early days of the pandemic.

Zoom fatigue. Been declining all week requests lately. 😫 pic.twitter.com/lB5XM7udy6

— The Nap Ministry (@TheNapMinistry) April 11, 2022

Last year, the Harvard Business Review partnered with business services company BroadPath to explore the factors that contributed to Zoom fatigue. The study found that use of front-facing cameras in video meetings was positively correlated with increased employee fatigue.

Similarly, an April 2021 study by remote work company Virtia found that more than 49% of workers reported being “exhausted” due to being on camera during meetings.

And while the volume of virtual meetings surely plays a part in employees’ remote work fatigue, it’s important to consider the impact of the on-camera factor when it comes to accessibility. Implementing a mandatory camera-on policy for video meetings can mean discriminating against your disabled and neurodivergent employees.

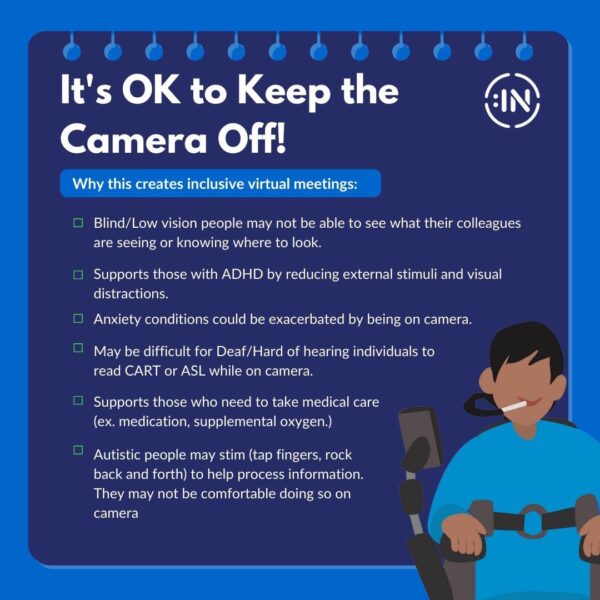

Disability:IN, a business disability inclusion nonprofit, often shares strategies for making the virtual workplace more accessible, which includes allowing employees to take meetings with their cameras off.

The nonprofit notes that requiring on-camera meetings could negatively affect employees who are deaf or hard of hearing, blind or low vision or those who are not neurotypical.

An infographic from Disability:IN examines the potential repercussions in more detail:

When your actual video background just won’t cut it

Being on camera can mean heightened awareness of your surroundings — and worrying about what your colleagues think of them.

“When you know that there is another human being who is watching and tracking you, it becomes a very evaluative experience,” Roshni Raveendhran, assistant professor of business administration at the University of Virginia, told The New York Times. “And once it is an evaluative experience, it kind of goes downhill from there.”

https://twitter.com/emmaleersmith/status/1518605592830648322

So, if your kids are running in and out of your home office or the room you’re working from is a mess, you’ll likely be at least a little stressed about what your coworkers must think of you.

Green-screen-like backgrounds and blurs can help mitigate this issue, but the tech is often glitchy and can look unprofessional.

Video meetings and self-objectification

Requiring employees to show their faces during meetings can actually encourage misogyny, too — but not in the way you might think.

In an essay published to Fast Company, psychologists Roxanne Felig and Jamie Goldenberg explain the rising phenomenon of female self-objectification during video calls.

“Because women and girls are socialized in a culture that prioritizes their appearance, they internalize the idea that they are objects,” Felig and Goldenberg write. “Consequently, women self-objectify, treating themselves as objects to be looked at.”

https://twitter.com/hannahtindle/status/1328444443205267457

Self-objectification can lead to negative consequences like facial dissatisfaction, disordered eating and even depression, they write.

In essence, spending all day on Zoom meetings with your camera on is like spending the day staring at yourself in a mirror. It’s not good for you — and it’s especially harmful to the mental health of women and girls.

If your C-suite expresses dismay at the number of black boxes on their screens during a video meeting, encourage them to think critically about why employees may have their cameras off. Creating an environment where workers feel comfortable turning off their webcams is about building trust between your C-suite members, managers and employees.

Try conducting an anonymous pulse survey of your workforce. Ask employees if they’d prefer to have the choice to be off camera during meetings, and when they think it’s appropriate for their colleagues to do the same. Ask for specific reasons that employees turn their cameras off. Once you collect and analyze that data, bring it to your C-suite (along with this article) to help support your argument one way or the other.